The only way out of the situation in which Russia has shown its true essence is for the West — to stop making its policy towards Ukraine a point of its policy towards the Russian Federation and make Ukraine a member of NATO in 2024. This is the opinion of Ian Kelly, the former U.S. ambassador to the OSCE and Georgia. As part of the project «Ukraine to the World» for Independence Day, Forbes asked him to tell, how the war in Ukraine changed the Westʼs attitude to global security.

Купуйте річну передплату на шість журналів Forbes Ukraine за ціною трьох номерів. Якщо ви цінуєте якість, глибину та силу реального досвіду, ця передплата саме для вас. У період Black Friday діє знижка -30%: 1259 грн замість 1799 грн.

In the wake of the collapse of the Soviet Union, the United States had great expectations for its relationship with Moscow.

But its relationship with Kyiv was more complicated: while supportive of Ukrainian independence, Washington made it repeatedly clear that its relationship with Kyiv took a back seat to the U.S. goal of cooperating with Moscow.

- Категория

- Рейтинги

- Дата

To cherish a snake in oneʼs bosom

In the early years of independence, George H.W. Bush and his successor Bill Clinton saw an historic opportunity to integrate Russia into the Western community of peaceful, cooperative nations. After the unraveling of the USSR, four countries had nuclear weapons: Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, and Kazakhstan. Fearing nuclear proliferation, both presidents prioritized reducing the number of nuclear states from four to one — the one being, of course, Russia.

Belarus and Kazakhstan quickly and willingly gave up the nuclear weapons on their territory. Ukraine, however, was divided on the issue, seeing the value of the weapons to deter future aggression.

Washington’s policy decision was based on a false assumption that Russia would become a benevolent international actor. Policy-makers saw the first president of Russia, Boris Yeltsin, as a defender of democracy, and the policies of his regime as a departure from the aggressive expansionist policies of his Kremlin predecessors. In 1991 the U.S. embassy in Moscow reported that Yeltsin was «committed to constitutionalism and democracy».

Newly independent Kyiv had a different perspective on Yeltsin. They recalled that in late August 1991 a statement released in Yeltsin’s name threatened that if Ukraine declared its independence, the Russian Federation would call into question Ukraine’s existing borders. With an eye towards reclaiming lands like Crimea and the Donbas, Yeltsin sent his Vice President, Aleksandr Rutskoy, to Kyiv to convince the Ukrainians not to declare the sovereignty of Ukraine within its existing borders.

The Ukrainians stood firm, and Yeltsin backed down. But Kyiv no longer trusted that Yeltsin, much less any future Russian leader, would respect Ukraine’s territorial integrity.

For its part, Washington put its faith in Yeltsin’s reputation as a democrat and a constitutionalist. President Clinton was even willing to condition U.S. support for Ukraine on Kyiv’s willingness to give up its nuclear deterrent against Russia. To underscore that point, Clinton told then-Foreign Minister Zlenko that he would not receive President Kuchma until he agreed to denuclearize. (Hearing this, Kuchma cancelled his visit to Washington.)

Illusory security guarantees

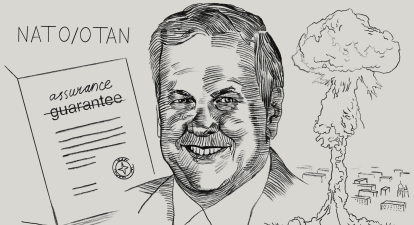

As we all know, Kyiv did agree to give up its weapons but sought from the West security guarantees for its territorial integrity, in return for giving up its nuclear deterrence. In the negotiations for a final agreement, the U.S. objected to the use of the word «guarantee», preferring the non-legally binding word «assurance», while not objecting to the word «гарантія» in the Ukrainian text and «гарантия» in the Russian text.

Moscow agreed to respect Ukrainian sovereignty when it signed the Budapest Memorandum in 1994, but knew Washington was not serious about providing firm guarantees to Ukraine. Aware that the Budapest Memorandum provided no security «guarantees», just mere «assurances» Putin drove a tank through the huge gap between those two terms when it violated Ukraine’s territorial integrity in 2014 and again in 2022. By not providing those guarantees in 1994, or in 2008, when Ukraine membership was on the table at a NATO summit, the West signaled that Russia’s neighbors were considerably less important than Russia itself.

The snake bit, but did not kill

Unfortunately, concerns about Russia continue to shape U.S. policy toward Ukraine. While the Biden administration deserves credit for providing huge numbers of weapons to Ukraine (the Obama administration wouldn’t give Ukraine any lethal weapons for fear of provoking Putin), it has not given Ukraine what it needs for more certain success in the ongoing counteroffensive: long-range artillery and the aircraft it needs to gain air superiority over the battlefield in Ukraine.

Washington has stopped short because of a fear of Putin. The assumption appears to be that Putin would trigger a larger war if Ukraine used U.S. weapons to strike inside Russia itself. There’s a certain paternalism inherent in the refusal to give Ukraine these weapons: it’s as if the U.S. is saying, «We donʼt trust you not to use our weapons to strike inside Russia».

Thereʼs also a moral aspect to this, particularly in the refusal to provide the air equipment Ukraine needs. The West blessed Ukrainian plans for their offensive, knowing full well we would not have sent our own troops into an attack without the proper assets. As a retired U.S. Army officer told the Wall Street Journal in July, «America would never attempt to defeat a prepared defense without air superiority, but they [Ukrainians] don’t have air superiority». President of Ukraine Volodymyr Zelensky is reported to say in the same Wall Street Journal article that «a large number of soldiers will die» in the attack because of the lack of air cover.

In short, for both moral and strategic reasons, the policy of subordinating our support for Ukraine to our policy toward Russia must finally end.

All weapons in our conventional arsenal must be made available. The lack of the full range of conventional weaponry is prolonging the agony of war and undermining our overall strategic goal of ending Putin’s brutal invasion.

Finally, even when the war ends, there will be no lasting peace or stability in Europe until the West provides legally binding security guarantees. The best way to do that is to provide Ukraine with NATO membership, with the Article Five protection the treaty provides.

The next NATO summit is in Washington in 2024. What better place to grant Ukraine NATO membership, signaling to Moscow that the Western community is indivisible, and Ukraine is an integral part of it?

Вы нашли ошибку или неточность?

Оставьте отзыв для редакции. Мы учтем ваши замечания как можно скорее.